Welcome to the

ideas collection

If you’re a member, you can access all benefits by clicking “members” in the navigation or “Account” at the top right on desktop or the drop down menu on mobile

Saturn & Sound as the Black Sun

Saturn represents the boundary between the visible and invisible—a liminal threshold where the known meets the unknown. Quite literally, it is the final planet visible to the naked eye in our solar system, a being which marks the edge of perception. Symbolically, Saturn is thus the frontier of the hidden self. When described as the Black Sun, a term that Saturn is associated with, it allows Saturn to transcend its physical identity and become a metaphysical force: a space where patterns of the unseen dwell, waiting to be brought into awareness.

The Black Sun is not an external phenomenon but an archetype existing as a paradoxical light that shines from within darkness, a source of insight emerging from the void. In astrology, Saturn’s placement in Capricorn and Aquarius lies opposite Cancer and Leo, the realms of the Moon and the Sun. The Black Sun, therefore, sits in contrast to our actual celestial Sun, revealing the relationship between inner light and shadow—the self and the unknown.

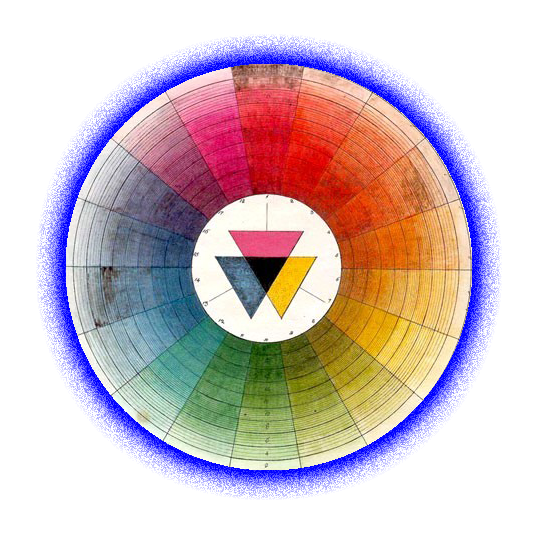

To understand this further, the astrological wheel reveals patterns that map onto the seven stages of alchemy. These stages, from nigredo to coagulation, form a bridge between night and day—sound and light. The nigredo phase—a symbolic dissolution and purification. It is the necessary decomposition of the old self so that a new, conscious form may emerge. The seven stages of alchemy mapped onto the astrological wheel move from Capricorn/Aquarius to Leo. More on this later…

Back to the houses…Interestingly, Saturn’s connection to the 10th and 11th houses on the astrological wheel reflects this duality. The 10th house of “career” is where we are most visible to the world but also represents the house that is furthest from the ground, and in the alchemical sense, the beggining steps in the process of self-actualization. There’s a lack of foundation in the 10th and 11th houses—a lack of stability. These houses exist outside of our “personal” and lives and are often representative of aspects of the self which are least known to ourselves. The Black Sun, then, invites us to confront these unseen truths, both within ourselves and mirrored in the world around us.

The paradox of Capricorn and the 10th house teaches that material and spiritual success are not opposites but interconnected. The highest point in the chart demands the deepest roots. To truly rise, one must

The Meaning of Life as Meaning Itself…

When we ask, “What does something mean?” we’re really asking how it fits within a broader context. Meaning is never an isolated event but rather a concept situated between ideas, experiences, or perspectives. Interestingly, the word mean itself holds a duality between language and mathematics. In language, meaning deals with interpretation and understanding, while in math, the "mean" represents balance—the midpoint between two extremes. Perhaps the meaning of the term mean, meaning itself, and the meaning of life are all interconnected in a self-referential loop.

The word meaning is rooted in the Old English mænan, which means “to tell” or “to intend.” Over time, it evolved from simple communication into a philosophical and linguistic question: What is the significance of this? What does it represent? Meaning has become synonymous with understanding, interpretation, and the human need to contextualize the world.

In this sense, meaning is something we assign or derive, a way to place things within a framework of understanding. When we try to comprehend something—whether it’s a piece of art, a moment in life, or a sentence in a book—we are attempting to position it between what we already know and what we don’t yet understand. Meaning becomes a bridge, connecting the familiar and the unknown.

Mathematical "Mean"

In mathematics, the word mean refers to the average (kind of)—the central value in a set of numbers, equidistant from the extremes. For example, in a data set of {2, 4, 6, 9, 11}, the mean is 6, the number that balances the lowest and highest values. The mean offers

Fibonacci Sequence, Beginning with a ‘New’ Number?

I love using and exploring the Fibonacci sequence in my work, but something about it has always bothered me. Traditionally, the sequence begins as follows:

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13,…

What is strange to me are the way the sequence begins and how the first two numbers, 0 and 1, break the sequence's own defining rule—that each term should be the sum of the two preceding terms. When you look it up, you often see explanations like “it has to start somewhere.” This answer doesn’t feel entirely satisfying. If the sequence is truly based on self-propagation, shouldn’t it begin with a value that inherently satisfies its self-referential nature?

There’s an obvious truth that the meaning of the sequence is “correct” as it carries weight in the natural world. People have explored this at length — from sea shells to human bodies, the Fibonacci sequence exists materially everywhere in nature. However, to this point, shouldn’t the beginning of the sequence satisfy the rules of the sequence itself? If anything, it’s imperative for the Fibonacci sequence in particular because part of our interest in the sequence is it’s fractal nature.

Look, I get it. The sequence required the jumping off point to even exist in our reality until this point. However, maybe we can explore the Fibonacci sequence in a way that uses paradox — if anything, to me, having the sequence begin with a paradoxical “number” or symbol might unlock some deeper truths about the birth of our physical reality.

On the I Ching & Yi-Globe in Relation to Light & Sound

Terrence McKenna thought of the I Ching as representing elements in the Chinese physics of Time. He said, while the Western mind was focused on what things are made of, the Chinese were more concerned with why things happen as they happen. In other words, the Western mind was focused on matter, while the Chinese were focused on the flux of matter—the change as matter moves from one state to the other: Time.

When we think of sound, we often consider it as a phenomenon rooted in matter—a vibration through a medium—but what if we start to view sound in relation to time? In many ways, sound gives us a temporal dimension to reality. Music, for instance, requires time to “function.” The affect of music is only possible to experience through time, as it is the perception of change from one note to the other. Just as film tells a story through a series of sequential frames, music unfolds in time, as the affect we experience when listening to music is inextricably linked to the experience of time progressing.

Without time, music would lose its structure. The lack of time would result in an explosion of notes occurring all at once, producing a cacophony of noise—a disturbing simultaneity that we cannot make sense of. Instead, music’s power lies in its sequential nature, where past notes blend into present ones, and the listener is constantly anticipating what comes next. This creates a feeling of movement through time, much like how our broader human experience unfolds as a continuous narrative.

In a more material sense, sound is often described as vibrations, a wave motion through a medium like air, liquid, or solid. Physically, sound isn’t a “thing” but an effect—a process, a relationship between pressure and matter. McLuhan’s phrase, “The medium is the message,” takes on new meaning here: the medium (the air or material that carries sound) shapes the experience of sound itself. Sound doesn’t just pass through the medium—it is the medium in motion, manifesting as a wave of pressure that we experience through our senses.

Therefore, sound, much like time, is not a static entity but an ongoing transformation: a temporal flux that connects our perception of the material world with the process of change. In the context of the material world, sound would be better linked with a thing’s form rather than a thing’s material make up, as form is more so about the relationship between elements of matter rather than the matter itself. It’s like in the context of architecture, light (or particles of matter) would be the building blocks, and sound would be the relationship and proportions between the building blocks. We might confuse the building blocks of being the form itself, but it is really the space which allows the form to exist at all. Space is separation which can only exist in three-dimensions through time. What we consider to be form is a particular way in which a thing exists or appears; a manifestation. In short, things are made up in a particular configuration which is experienced over time.

This notion of light and sound in the context of matter and form is quite interesting when you conflate them with ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ focus on the Sun and Moon respectively. To McKenna’s earlier point,

Time as a Fourth-Dimensional Artist

Dimensions can be viewed as both enablers and limiters in our perception of reality. Each dimension offers a framework through which we experience and understand the world, but in doing so, it also imposes boundaries that shape our interpretation of what we perceive.

For example, we live in a 3D world where depth, height, and width define the objects around us. Our perception of three dimensions gives us the ability to navigate, understand, and interact with the physical universe. However, when we translate a 3D object into a 2D representation, such as in drawing, painting or even graphics on a computer screen, we strip away one dimension—usually depth—leaving only height and width. Any representation which appears 3D is an illusion happening in the 2-dimensional plane. Creating in the 2-dimensional plane forces us to interpret that object differently, flattening the experience but also giving us new ways of representing ideas.

In 2D media like cartoons or comic books, the absence of depth paradoxically allows us to stretch the boundaries of reality. Characters can defy physics, proportions can shift, and the impossible becomes possible because the dimensional limitation invites new creative liberties. The reduced complexity offers a more symbolic, abstract perspective. In many ways, the limitation of a lower dimension gives space for higher imaginative freedom.

Through these dimensional translations, we also discover that each dimension contains within it the seeds of others. For example, a shadow is a 2D projection of a 3D object. Similarly, by working within the constraints of lower dimensions, we can perceive aspects of higher dimensions—though indirectly or through symbolic means. This interaction between dimensions highlights the complex interplay between freedom and limitation, where restricting one aspect of perception opens new possibilities for seeing the world differently.

In this sense, dimensions act as both filters and lenses. By constraining our viewpoint, they simultaneously offer new perspectives that we wouldn't access otherwise.

The fourth dimension, often conceptualized as time or a higher spatial dimension beyond our three, introduces a fascinating dynamic when viewed through the lens of perception and limitations. Just as 2D represents a flattened version of 3D reality, the fourth dimension could be seen as a framework that shapes and influences the possibilities within 3D space, but in ways we might struggle to fully comprehend with our current perception.

On the Fool, the World, the Centre and the Circumference

⊙

Like all good symbols, all aspects of the symbol above are significant: the centre and the circumference are interdependent. In the context of the Tarot, the World and the Fool card are both expressing idea of being the centre and the circumference simultaneously. As Guénon points out, the circumference and the centre require each other; without the fixed centre, the circumference cannot rotate, as the centre is the “unmoved mover” for the circumference. Without the circumference, there is nothing for the centre to be a centre of—it would just be a random point in space without definition. The circumference literally defines where and what the centre is. To that avail, what Guénon is suggesting is that the classical symbol for the Sun, as seen above, is actually more of a World Axis or Polar symbol rather than a Solar symbol. This is because the symbol itself evokes the idea of rotation or wheel, which is most akin to how we observe the heavens’ rotation around the Pole Star.

If you think about it, there is no wrong interpretation of the symbol (Solar or Polar), it’s just a matter of what perspective you’re choosing to observe it from. If we take the Solar perspective, and that the Earth is revolving around the Sun, the Sun is the centre point and the Earth is the exterior circumference. If we take the Polar perspective, the centre would be the World Axis, or Earth itself, and the circumference could be the rest of the heavens which revolve around the Pole Star.

How does this relate to the Fool card?

This is quite interesting in the context of the Fool and the World. As mentioned, they both have centre and circumference symbolism within them (in both the Marseille and Rider-Waite decks). The Fool is the unnumbered card in the Marseille deck, and the zero card in the Rider-Waite deck. Whether it is zero or unnumbered, the Fool is often considered to be a “point of departure” for the entire Major Arcana. The zero, having no value, is dimensionless—literally a point that is immoveable. Even mathematically the zero always “returns to itself”—everything multiplied by zero is zero. Dividing by zero is a whole other problem with a similar ending. Zero, too, is considered the axis of the number line—the dimensionless point which separates

Quintessence: On The Relationship Between Venus, Phi and Five

Quint-essence, literally means fifth essence or fifth element. The word quintessence is also related to the word quintessential of similar origin which is defined as representing the most perfect or typical example of something.

The five (5) is the number of the macrocosm of human experience. As we will uncover more deeply, it is also related to various sacred geometric proportions. One of them is the infamous golden ratio, or Phi (Φ), whose proportion is based on the square root of 5. The golden spiral, as seen below, has a growth factor of Φ. The relationship of the number Φ and growth is also visually apparent when we look at many plants, flowers and animals, and as such the 5 in the context of the golden spiral is the number of solar growth. Outside of the golden ratio, the 5 plays a role in our physical and spiritual bodies: our material bodies are made up of 5 appendages (the head, the two arms and two legs), we have 5 fingers on each hand and 5 toes on each foot, and we experience the world primarily through the 5 senses of touch, hearing, sight, smell, and taste.

The ‘5’ is the number of experience, as the fifth element adds the layer of essence to the material world. The etymology of the word essence is from Latin essentia meaning "being". Originally, the essence character of something was mainly used in the context of perfumes; it was the “ingredient which gives something its particular character". The 5 is the essential character of a being. The 5 makes the world worth experiencing, through

A Language of Measure & Our Perception of Space

As Juhani Pallasmaa writes in The Eyes of the Skin, “the most archaic origin of architectural space is in the cavity of the mouth, through which the infant first experiences the world.”

Our experience of the world is fundamentally shaped by how we perceive space, which is essentially our three-dimensional reality. The methods we use to measure and understand space influence our experiences by shaping and sometimes limiting the primary senses through which we interact with our surroundings. Consequently, people perceive space—and, by extension, the world around them—in diverse ways depending on their primary sensory apparatus, leading them to inhabit significantly different sensory worlds.

Proxemics is the term that Edward T. Hall coined for the study of the ways humans utilize and perceive the space around them. In the opening paragraph of his book The Hidden Dimension, Hall discusses the nature of language and how studying languages different than one’s own is difficult, as language acts as a kind of thought barrier:

“It was necessary for the linguistic scientist to consciously avoid the trap of projecting the hidden rules of his own language onto the language being studied.”

Language itself was then discovered to not just be a way to externalize thought, but was rather a program that was restructuring the way people conceived of the world around them.

“Like the computer, man’s mind will register and structure external reality only in accordance with the program.”

What Hall is interested in, in this vein, are the ways in which different cultures not just speak different languages and thus have different thought constructions, but also how different cultures—as a result of their proxemic differences—develop siloed sensory screens through which they perceive and construct the world. This is interesting to consider, as the perception of space is a perception of separation. As discussed in On Understanding the Void through Dividing by Zero, in order to measure space, one requires a reference point. Infinity itself is not really a number but a spatial concept. Space naturally requires division in order to be perceived. Without division, there would be no magnitude of anything, but infinitely everything. You could think of the literal definition of infinity as “without limits”: we require limitations in order to measure space. For example, “units” is a set of defined measurements that we use to measure other defined things. These units are ultimately reference

Monarch Meds #2: the Felt-body & the Skin

Monarch meds (meditations) is a series where I instinctively select two books and then, in a stroke of serendipity, open each to a random page.

Subscribe to read the texts referenced in this article.

These texts when read conjunctly speaks to universals of the human condition, straddling the realms of physiology and phenomenology to reveal how skin holds threads of emotional, physical, and existential elements. Tonino Griffero, in his passage, is advocating for an understanding of human experience and ethics that is rooted in our embodied existence. He challenges traditional dichotomies between mind and body, internal and external, suggesting that our emotions, expressions, and ethical lives are all interwoven aspects of our being in the world. Edward T. Hall, interested in the skin, portrays the organ for what it really is: not as merely a boundary or shield but as a dynamic interface for communication. He speaks to the skin itself as a living being, sensitive to the ebb and flow of emotional states. This scientific insight into the skin's capacity to emit and detect heat resonates with the Griffero’s idea of the felt-body as an arena of knowledge. Here, the body is not a passive vessel but an active participant in the world, embodying and expressing our being in a way that transcends dualistic conceptions of inside and outside.

This is fascinating when speaking to the concept of what is knowledge and what is knowing. We sometimes conceive of the world as happening to us, like we are in an environment and then our personal, internal senses perceive the world around us, which then impacts our internal states of being. If we think about ourselves like this, we are, in a sense, buying into the dichotomy of inside vs. outside—mind vs. body. We start to believe that the external world is separate from ourselves, and thus knowing it would too happen in an external plane. Perhaps, though, our internal states actually effect the external environment in a kind of

On Libra, Beauty and Justice

Everyday at two o’clock, people gather at the Bowes Museum to observe the winding up and subsequent performance of the 250 year old Silver Swan. Three clocks—one for the glass water, one for the music box and one for the swan—activate the performance where 30 pounds of silver move within a bed of twirling glass rods, wherein flickering silver and gold fish swim. Crafted to be an “exact replica” of a female mute swan, every detail of the swan, from each carefully made feather to the shimmering glass water it swims in, is a work of art. The feathers, resembling silver leaves, mirror the bed of delicate silver folds which are placed around the base of the artwork like a horizontal frame. These flecks of silver hide a series of complex mechanisms which drive the movement of the swan, water and generate atmosphere through music. Yet, as we watch, the mechanics seem to disappear, leaving us in awe of a spectacle that breathes life into metal.

The renowned American writer Mark Twain documented his observation of the swan in a section of The Innocents Abroad, where he described the swan as having “had a living grace about his movement and a living intelligence in his eyes."

What we are seeing as an observer of the Silver Swan is not the concept of what a generic swan is, but rather the Silver Swan captures the essence of a very particular moment of a particular swan, immortalized in silver and glass. You could think of the human who winds up the swan, then, as not winding up, but rather winding back time for everyone to observe that particular moment replicated ad infinitum.

As J.F Martel describes in his book Art in the Age of Artifice, beauty always concerns the particular. Something is always beautiful in this moment or time— always in the singular. The swan is beautiful not because it is a “perfect replica” of a generic swan, but rather because it is THE Silver Swan—a singular being. At its core, the creators, John Joseph Merlin and James Cox, were driven by a desire to emulate the natural spectacle where water and sky, sea and bird, glass and silver, intertwine in a graceful dance. This creation is not just of the physical swan, but the replication of movements which are too immortalized as mechanical clockwork. This clockwork breathes life into that immortalized experience of the sky and water merging, as the swan sits peacefully on the glass rods and dips it’s neck into the glass substance to retrieve a fish. This act of replication goes beyond

On Understanding the Void through Dividing by Zero

A lot of the following ideas are built on notes from a great podcast episode called Zeroworld from Radiolab. Listen here.

As you may have remembered from math class, we're taught that you can do almost anything with the medium of numbers, except divide by zero.

That’s because in math, division by zero is undefined. Here’s two simple points as to why:

Division is fundamentally defined in mathematics as the inverse of multiplication. For example, 6/3=2 because 2*3=6. However, when you try to apply this to division by zero, things fall apart. A key concept of math is that things need to be "undone", but there is no number that you can multiply by 0 to get a non-zero number, and therefore division by zero cannot be "undone" through multiplication. Therefore by allowing division by zero, it would create contradictions within mathematics. For example, if you were to define 1/0 = some number, let's say 'Y', then according to multiplication, 0*Y should be 1. But we know that anything multiplied by 0 is 0, so this breaks the basic rules of arithmetic.

When you divide a number by another number that gets closer and closer to zero, the result becomes larger and larger, approaching infinity. The problem with this is infinity is actually not a real number; it's a concept. Dividing by zero doesn't produce a definable number but rather leads towards an infinite limit, which is not a specific, finite value.

For example:

1/1 = 1

1/0.1 = 10

1/0.01 = 100

1/0.001 = 1000

and so forth

Therefore, as we divide something with numbers that approach zero, the result approaches infinity.

This relationship between zero and infinity can give us insights into another reason why division by zero is “not allowed” - when we divide something by zero, we’re actually getting an answer that’s not a number. Remember, infinity is a spatial concept. Maybe, then, division by zero is actually a portal into understanding their inextricably linked qualities.

Zero & Infinity

As Charles Seife states, "Zero and Infinity are two sides of the same coin--equal and opposite, yin and yang, equally powerful adversaries at either end of the realm of numbers". The essence of zero cannot be fully appreciated without its counterpart, infinity, and vice versa. Their interdependence is such that the presence of one suggests the existence of the other.

Zero represents a numerical foundation, a point of origin. In mathematics, it's the central point in the number line, demarcating the positive from the negative. As a number, zero signifies nullity or the absence of quantity, which is essential in arithmetic and algebra for maintaining the integrity of the number system.

Infinity on the other hand, is often perceived as a spatial concept. It represents boundlessness or unending extension. In geometry and calculus, infinity is used to describe endless lines, curves, or surfaces. It's not a number in the conventional sense but rather a state or quality of being limitless. In math, infinity is used to describe the behaviour of functions as they stretch out towards endlessness. In physics, infinity is used to describe concepts like infinitely small scales (quantum mechanics) or infinitely large expanses (cosmology). Infinity's relationship with zero in this sense is clear, where operations involving limits explore how functions behave as they approach zero (infinitesimally small) or stretch towards infinity.

A math concept that discovered an interesting relationship between zero and infinity is the Riemann Sphere. Imagine a sphere sitting in a 3D plane, where

On the Solar Tree & the Lunar Rhizome

The score of Piece Four for David Tudor by Sylvano Bussotti serves as a prefatory image to Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus. In essence, it’s a perfect image to “start off” the work (though there is really no beginning nor end) as Bussotti’s score could be seen as a microcosm of the work as a whole.

It functions so well as a prefatory image to this work because it merges the seen and the unseen; the known and the unknown. The existing framework of the piano score is key to the image’s success. Even someone who does not play the piano can understand that this is a creation birthed from the existing framework of a music score, since the graphic essence of a sheet of music is universally understood, even just as a graphic artifact.

Why should we care about this?

The ideas within Deleuze and Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus challenge traditional ways of understanding and organizing knowledge. They question linear, hierarchical structures that have dominated Western thought, suggesting these are too limiting to capture the complexity of reality. Bussoti’s diagram too is clearly challenging the existing framework and structure of music notation. He is quite literally breaking through the boundaries of the language of music in order to convey the music he really wills to produce, which is beyond the scope that ordinary musical notation can capture. According to Deleuze, a great writer always acts like a foreigner in the language in which they express themselves. Even if it’s their native tongue, they do not mix another language with their own; they must carve out another foreign language within their own. What does this mean? A great artist doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel; perhaps simply reframing the wheel in a new context. In Bussotti’s case, he is using the language of music and carving out his own space within it.

To dig into Bussotti’s diagram further, we should discuss two key ideas in A Thousand Plateaus: Deterritorialization and reterritorialization. Deterritorialization refers to the process of breaking away from or undermining traditional, often rigid, social, cultural, or intellectual boundaries. It involves the unraveling or deconstructing of established structures and relationships, leading to a fluidity and openness that inevitably challenges conventional norms and classifications. This process enables new connections, meanings, and identities to emerge, often in unexpected or non-linear ways.

Reterritorialization is the process that follows deterritorialization. It involves the formation of new structures, boundaries, and meanings as a response or adaptation to the disintegration caused by deterritorialization. This reconfiguration doesn't necessarily mean a return to previous states or structures; rather, it signifies the creation of new territories, systems of thought, or social relations that are influenced by the disruption of the old ones. The interplay of these two processes reflects the dynamic nature of social and cultural systems, where change is constant, and stability is often temporary. The concepts of deterritorialization and reterritorialization emphasize the fluidity of meaning and identity in a constantly shifting world, highlighting the transformative potential of disruption and change.

As Bussotti deterritorilizes the piano score, he is taking the entire language of music and subverting it’s existing structure to create something new. It is the past and present collapsing to create

On the Vedic Square & the Sacred Number 9

A visual guide to the vedic square and the vedic cube to show the harmonious relationship created by the number 9…

On Numbers and the Gamification of Media

In our contemporary culture, media of all kinds resort to numbers as the authoritative language to create data sets, analyse information and measure progress. The pursuit of measurable success is emphasised, with hard work being touted as the only path to achieving it. We can understand this through societal standards of success, which try to ensure that happiness is an objective measure and it exists someplace far in the future, promised only to those who work hard enough to achieve it.

While this culture of control persists, the world of chance and luck also thrives as casinos and online gambling platforms entice us with the allure of being able to strike it rich by getting lucky, even if the odds are often stacked against us.

These two dichotomous worlds are happening in parallel: the culture of control and the culture of chance. The former emphasizes the power of luck, fortune, and grace, while the latter emphasizes rationality and predictability. Numbers of the medium which mediates them both.

The allure of gambling and the culture of chance is rooted in human fascination with the apparent randomness and unpredictability of the universe. Gambling, in some ways, represents an attempt to impose order and predictability onto a chaotic system, by calculating odds and tracking wins and losses. The ability to predict and control the outcome of chance events, no matter how small, provides a sense of mastery and control in a world that often feels uncertain. In this sense, gambling could be considered the gamification of the universe itself. What humans perceive as randomness in the universe is turned into a structured event where we can measure the odds of a dice roll, roulette ball rolling into place or the odds of getting dealt the perfect poker hand.

Through the lens, we can see how all media

Monarch Meds #1: Psycho & the Coniunctio

Monarch meds (meditations) is a series where I instinctively select two books and then, in a stroke of serendipity, open each to a random page. Similar to Tarot, I would consider this a kind of “designed chance” experience. The experience of pulling out the deck with the intension of doing a reading is designed, and then the subsequent chance event occurs. The passages chosen by chance are taken delightfully out of context, with the purpose of bridging them (conceptually or otherwise) to hopefully generate something new. Today, we discuss the relationship between the alchemical process of the conjunctio in relation to the film Psycho.

Subscribe to read the texts

I had never seen the 1960s Psycho before, and even though the shower scene is so ubiquitous in pop culture, I naturally had to take the opportunity to watch the entire film. The obvious connection of these two passages, or even works of art in general, is death: the killing of the dragon and the killing of Marion.

The first passage from Alchemy & Mysticism is a reference to the Alchemical concept of the Coniunctio (or conjunction). The death of the Mercurial dragon can only be acheived through the coniunctio, or the unification of opposites: “killed by his brother and sister at once”. That is, in order to kill the Mercurial dragon one must remove their sulphur and lunar moisture at the same time. The passage of J.F already mentions the most interesting aspect of this: that the coniunctio could also be understood more primitively as sex and thus, life. The shower scene where Marion ultimately dies by the kitchen knife was shocking to viewers of the 1960s. The whole shower scene is 45 seconds long where we see the creeping of the shadow of Norman holding the knife, the curtain rip open, and the subsequent scenes that flash before our eyes which outline a clear rhythm of sex and death; naval and knife.

As J.F mentions, the knife, while a mundane object in the narrative, transforms into a symbol of deeper realities, encompassing themes of sex, violence, life, and death. It transmutes itself into a symbolic object which one could argue is itself a representation of the coniunctio in that moment. Though, if one were to claim the knife is entirely representative of the singular concept of the conjunction step in alchemy, it is through the integration, or unification, of sex and death that happens in the minds of the viewer. As Hitchcock points out himself, there are no

On the Invention of the Pigeon

In all animal history, pigeons have undergone the largest decline as a status symbol. These common birds are a prime example of how familiarity and abundance can alter external perception - from pigeons existing as a symbol of wealth and aristocracy to a symbol of uncleanliness and contempt. Even the word pigeon has developed a negative connotation. There was once a time when dove or pigeon could be used interchangeably. The dove, representing peace and associated to the holy spirit : “the third person of the Trinity; God as spiritually active in the world”. The pigeon, on the other hand, has developed the nickname skyrat, even though doves and pigeons are genetically indistinguishable.

The history of the modern-day city pigeon begins with its domestication. The domestication of an animal starts with selective breeding for a specific intention directed by various phenotypes. The domestic pigeon was breed from the wild “rock dove” – a bird that thrived in caves and rocky cliffs of Europe, Asia and Northern Africa. These pigeons thrived in buildings and around urban areas because of their history of surviving in rocky terrains. Since humans’ initial discovery that these birds were more than a food source, several distinct breeds have been “invented”.

Old Dutch Capuchine (Gardner 2019)

These pigeons were kept and domesticated for their beauty, their homing ability allowing them to become excellent messengers, as well as their taste. Dovecotes, or pigeon towers, are structures for housing pigeons. Because pigeons have a strong sense of home, there is no need to keep them captive. The pigeons would forage for food during the day and return to the pigeon towers in the evening.

English Pouter (Gardner 2019)

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the laws surrounding who was allowed to own a pigeon tower were strict. The ability to construct a pigeon tower was a privilege reserved for feudal lords. Around the mid- 1500s, if you constructed your own dovecote without proper permissions, you were ordered to have it demolished. The strict regulation of dovecotes resulted in their rarity in the urban landscape, augmenting the pigeon tower as a symbol of status. Another layer of hierarchy that manifested in built form was their size and ornamentation. The higher your societal class, the more pigeons you were allowed to keep and hence the larger and more ornate your dovecote was allowed to be. Once the ruling class laxed their laws on who was allowed to construct dovecotes and raise pigeons, their construction became more prevalent. The increase in the number of dovecotes that were constructed initiated their decline as a true status symbol. The prestige of the birds declined alongside them. Pigeons, due to their rich history, are a great example of commonality and extreme uniqueness existing simultaneously. Over the course of recorded human history, the genetic makeup of the common pigeon that thrives in cities around the world have not changed. What has changed are the way humans

Three Ideas on the Idea of “Normal”

Sophie Calle is a French writer and artist, whose work has generally focused on the human condition in respect to vulnerability and intimacy. “The Hotel” is a written piece based on an actual account of her becoming chambermaid at a Venetian hotel for three weeks. Sophie Calle writes “The Hotel” as a series of diary entries over the course of several days. The text expresses her idea of the users’ experience of Venice as a place through very generic objects and for their users’ intimate use within the hotel room. The objects within a hotel room, due to the nature of travel, become symbols of not just the most ordinary and most used objects of everyday life, but also the most extraordinary objects and things that are most cherished. Calle treats the very boring and familiar things, such as clothing and toiletries, as the protagonist of the story – the quintessential elements of peoples’ lives and that which provide a greater understanding of the people dwelling within the room.

The objects within the room are themselves interesting enough, as they showcase things which people “cannot live without” – ultra personal things of everyday life. Each person reading the text can relate to the types of clothing’s, books, and other common objects she refers to, but as well understand how the careful curation of the objects within our lives becomes a significant part of a persons’ self-identity. “The Hotel” series becomes an important piece in our own understanding of how ordinary objects come to define us from not only an external perspective, but also how we define ourselves.